Germany is set to go to the polls on 26 September to vote on who will sit in the Bundestag. But the most important, historical facet this time around is that chancellor Angela Merkel will not run. Her time in office is coming to an end.

There is an easy way to tell that voting in Germany is about to open. Everywhere, on every street in Berlin, is adorned with posters, all with pictures of people who you only see every couple of years. Vote for me and I will do that, Vote for me and I will do this. Those faces may change, but the messages stay the same.

I can see in my neighbourhood posters for the SDP, CDU, and the Greens. There are no posters for the far-right AfD party here, not surprising given the international neighbourhood. And even if they did appear, a pair of secateurs wielded late at night is another way to practise democracy.

End of an era

Merkel is the country’s third-longest serving chancellor after Bismarck and Kohl, but possibly has had more crises to deal with than any other. Since coming to power in 2005, she has dealt with the financial crisis of 2008-2010, the refugee crisis of 2015 when she opened the borders to over a million fleeing war and persecution, the Greek debt crises, and the current pandemic. And, even more recently, there have been the devastating floods in North Rhine Westphalia.

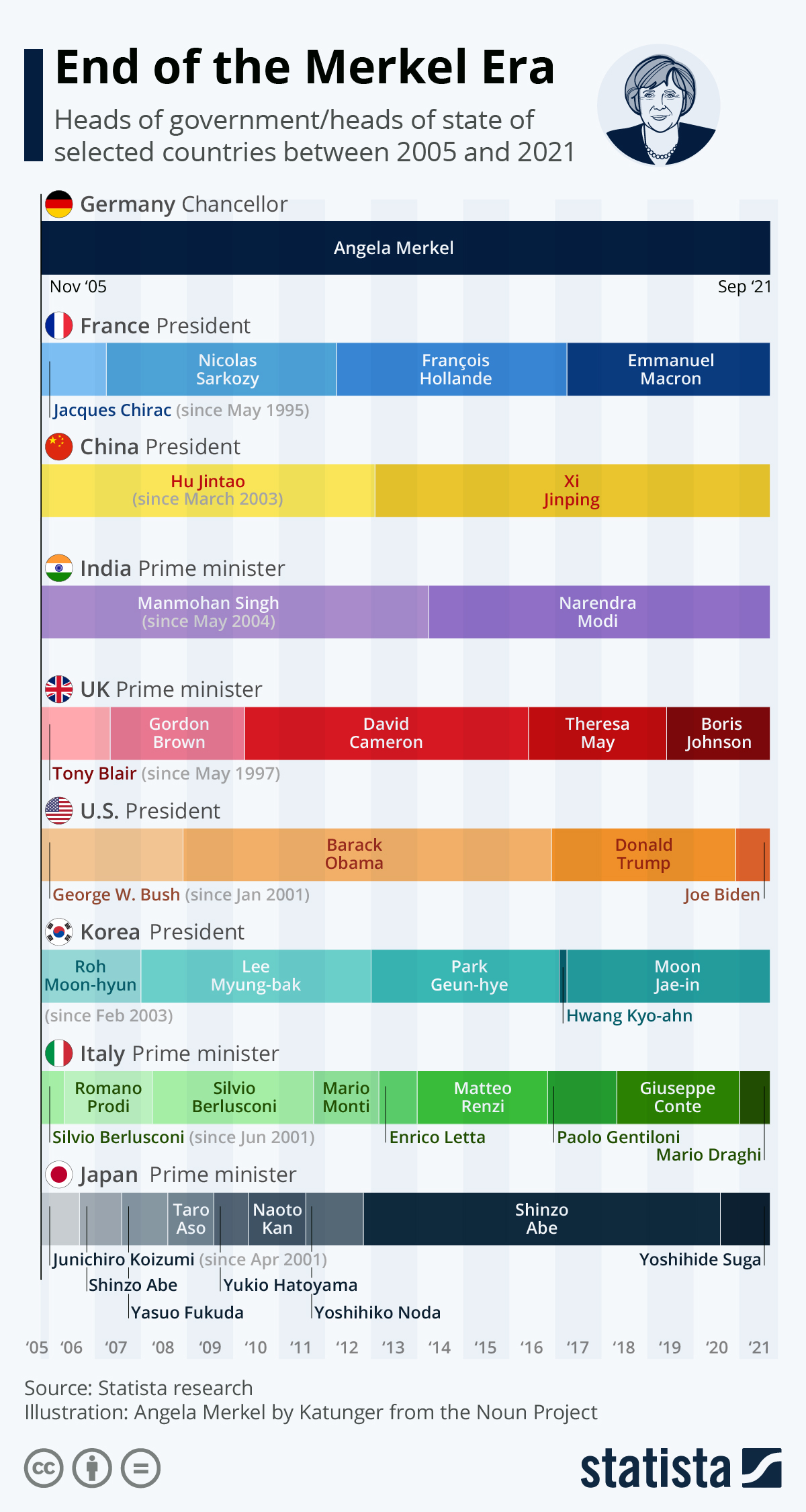

Her time in office overlapped with four American and French presidents, five UK and eight Italian prime ministers. For a full picture of her time in office, check out the image at the bottom of the page.

But Merkel will be gone soon, and there is no real frontrunner to fill her seat. She is, as The Guardian recently wrote, “[…] putting it mildly, a tough act to follow’.

The Guardian continues: “A two-way coalition between the conservative CDU and the German Greens had long looked the most likely outcome. However, neither party fared well in their response to the devastating floods that hit Germany in July, giving a boost to the confidence of smaller parties.”

Creeping covid

Merkel is not only a tough act to follow, but whoever steps into her place will not be dealing with a normal transition. Germany’s lockdown was much, much stricter than the UK’s and while that side of the water has pretty much returned to life as normal, there are still numerous restrictions in place here. As I write this, the local primary school has sent home its students to quarantine for 10 days after one tested positive over the weekend for Covid.

And the numbers are rising. According to data crunched by Worldometer, covid cases are once again going up. After peaking around 14 April, when there were 32,546 new cases each day, that number sank to between 300 and 500 over June. As of 21 August, it was back to 6,625.

After a vaccination programme that started unforgivably slowly before cranking into top gear, the rise follows a summer where many seemed to ignore the fact that a pandemic was still in mid-swing.

Some projections put the number of daily new infections at nearly 43,000 by October 11, two weeks after the next elections. Whoever comes after Merkel will not only step into the remains of this crisis, but will also deal with a populace exhausted from nearly two years of dealing with limited freedoms, restrictions, and vigilance. That is a tough hill to climb, especially as resistance to the measures grows (even if it does seem like revolutionary cosplay).

Reputation rethink

The economy has also taken a massive hit under covid, despite the multiple measures in place to alleviate the worst of it. Between January and March, GDP slid 1.8%, according to Deutsche Welle, on top of the 5% it sank in 2020. And although that 5% dip is not as bad as other countries, these things are all relevant.

Whoever the next chancellor will be will not have the same burden as Merkel when it comes to the pandemic. Hospitalisations are still low, compared to the numbers testing positive—a result of the vaccine rollout. But I suspect that the population are becoming harder to convince of the greater purpose in distancing and restrictions. Many suspect, and are not entirely wrong, that a higher price has been in some quarters than was necessary.

In broader terms, the new chancellor will have other issues to deal with. The refugee crisis of 2015 was a great test of popular opinion towards Merkel and was positive at first but soon turned toxic after the mass sexual assaults in Cologne on New Year’s Eve. An incumbent civil war in Afghanistan may soon reignite those concerns and I doubt the next Chancellor will throw open the doors like their predecessor.

All this makes me suspect that the domestic political scene in Germany is about to go through a period of strife, and it will be one that diminishes much of the country’s image on the world stage. Merkel has, at times, been the true leader of the Western world after its traditional incumbent forsook the magnitude of that task. Most people outside of these borders struggle to name the party she leads, never mind its opposition. Brand Germany in recent years has been built upon Brand Merkel. With her gone, things are going to get very interesting.

And not in a good way.