Various factors fuel the move towards dollarisation, but monetary stability is typically the primary catalyst among them. As such, nations facing economic turmoil, including currency devaluation and hyperinflation such as Ecuador and Zimbabwe, see dollarisation as a fast track to restoring economic equilibrium.

Meanwhile, countries with open economies and robust private sectors such as Panama, lean towards dollarisation to enhance trade and economic stability. We have analysed several case studies, and concluded that the reasons to dollarise, the process of dollarisation and the outcomes vary widely and lack a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

The key advantage of dollarisation is economic stability for countries with high inflation and unstable currencies. By adopting the US dollar, these nations aim to achieve price stability and a more predictable economic landscape, as seen in El Salvador and Ecuador in the early 2000s. This stability appeals to foreign investors and simplifies international trade by removing the need for currency exchanges, thereby potentially reducing costs and strengthening trade ties.

Furthermore, adopting the US dollar can enhance public confidence in the financial system, especially in scenarios where the local currency has been subject to significant devaluation. This confidence boost stems from several key factors.

First, banks’ balance sheets become stronger by eliminating the risk of losses from volatile local currencies, making the financial sector more robust. Second, the forced monetary discipline helps control inflation, making the public more inclined to save rather than spend quickly, thus stabilizing the economy. Thirdly, the predictability of the US dollar leads to more domestic and international investment.

A less-discussed benefit of dollarisation is that it acts as a stabilizing force during economic uncertainties, offering a protective layer that reduces the immediate need for capital flight.

While offering some benefits, the adoption of the US dollar also introduces significant drawbacks. One of the most critical is the loss of independent monetary policy. Countries that choose dollarisation forfeit their ability to steer their economy through adjustments in interest rates or currency valuation.

This loss severely limits their flexibility in responding to economic challenges and shocks, making it harder to tailor economic policy to the country’s specific needs. Another cost of dollarisation is the loss of seigniorage, or the profit earned from printing currency. It can lead to a decrease in the currency’s purchasing power and an increase in price levels, meaning there is a fine balance between printing money as a central bank and this becoming inflationary.

Case studies

Zimbabwe faced hyperinflation and the collapse of the Zimbabwe dollar in 2009 as a result of several critical events and policies that undermined the country’s economic stability. To stabilise the economy, the government introduced a multi-currency system in 2009 with an aim to restore monetary stability and foster economic growth.

Although the move to a multicurrency system initially stabilised the economy it led to unforeseen complications. As foreign reserves fell, the economy became heavily reliant on remittances and exports for US dollars. This dependency introduced volatility, with the flow of foreign currency being unpredictable and often insufficient highlighting a crucial precondition for successful dollarisation: the need of stable and substantial access to FX. The absence of such a foundation crippled the economy.

While the multicurrency regime reduced hyperinflation and brought some stability it led to reliance on volatile FX sources and diminished the central bank’s ability to effectively manage the economy. Despite some temporary improvements, the country eventually faced worsened GDP growth and a resurgence of inflation, highlighting the complex trade-offs of such a currency regime.

The ongoing efforts to reintroduce the Zimbabwean dollar and extend US dollar transactions until 2030 are aimed at finding a middle ground. This strategy seeks to leverage the benefits of dollarisation while addressing its limitations, all in pursuit of long-term sustainable growth.

Elsewhere, Ecuador’s experience of dollarisation revealed minimal effects of seigniorage loss, with lost revenues averaging merely 0.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) annually. This is a small trade-off for gained economic stability.

In contrast, while Argentina’s high inflation has significantly reduced its seigniorage, economists predict that dollarisation could result in an annual seigniorage loss for Argentina ranging from 0.6% to 0.8% of GDP. Despite this, the prospect of achieving economic stability and controlling inflation may well offset the losses.

The reality of the depth of Argentina’s economic crisis has prevented an immediate dollarisation, but the conviction to permanently stabilise the country’s economy by removing the Argentine peso from circulation remains a medium-term goal.

So, does it actually work?

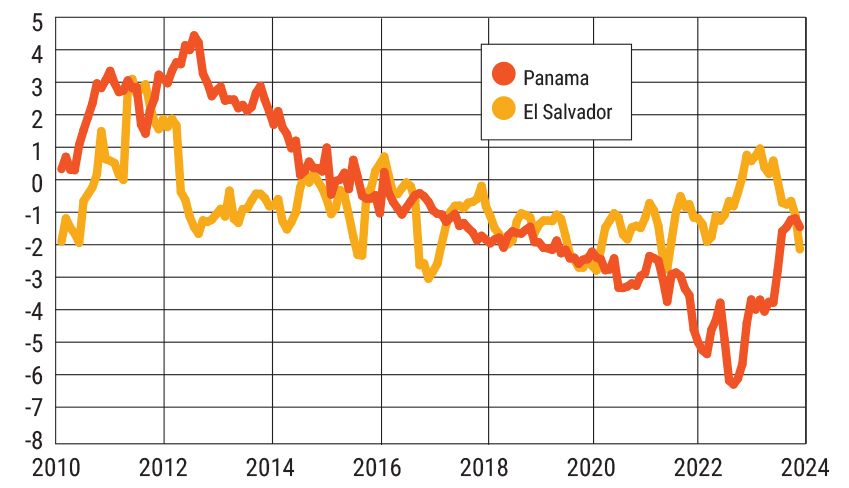

It is difficult to disentangle the long-term impact of dollarisation as the reasons for dollarisation are not exogenous. Despite this, it can be argued that most countries do see monetary stability and a subsequent fall in inflation. For instance, both Panama and El Salvador have seen periods of lower inflation than the US.

The small subset of countries that have dollarised have benefitted from lower inflation. Consumer Price Index (%)

Evidence suggests that countries that dollarise experience higher transfers from the anchor country, higher tourism and higher levels of financing compared to non-dollarised economies. There is also evidence to suggest that trade flows are higher in dollarised economies, although as pointed out already, a motivation to dollarise can be the already-close economic ties with the country of the foreign currency.

On the other hand, there does not seem to be much evidence of greater fiscal discipline in dollarised versus non-dollarised economies despite the lack of a lender of last resort. There is also evidence suggesting countries that dollarise experience slower and more volatile economic growth, with this partially attributed to a lack of monetary policy to adjust for economic shocks.

The impact on economic growth is seemingly mixed. Given the small subset of countries that have dollarised, it is difficult to draw hard conclusions other than that it has had a seemingly positive effect on these particular countries. Therefore, a country would need to assess their own unique circumstances before taking the leap to dollarisation and ensure it meets certain preconditions before it does so.

Nicholas Hardingham is senior vice president and portfolio manager at Franklin Templeton Fixed Income